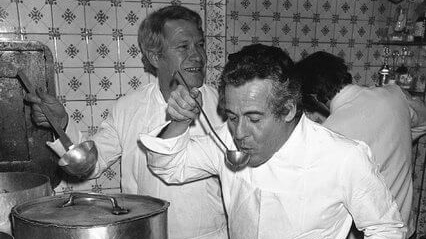

Christian Millau, a founder of the influential Gault-Millau restaurant guide, which led the way in making nouvelle cuisine a global force in the early 1970s, died on Saturday at his home in Paris. He was 88.

Côme de Chérisey, the managing director of Gault & Millau, announced his death.

Mr. Millau was an editor at the afternoon newspaper Paris-Presse in 1969 when he and one of his writers, Henri Gault, started Le Nouveau Guide Gault-Millau (pronounced go-mee-YO), a monthly magazine filled with restaurant reviews.

“We agreed on nothing,” Mr. Millau said in an interview last year for the Gault & Millau website. “Neither politics, nor religion, nor music. Nothing except taste.”

The upstart guide, aimed at younger readers with a yen for culinary adventure, took dead aim at the sedate Michelin Guide, which Mr. Millau liked to dismiss as “a telephone book.” He and Mr. Gault, who died in 2000, knocked revered dining establishments off their perch; elevated unknown, often humble bistros and cafes; and offered their readers freewheeling reviews, rather than Michelin’s terse lists of dishes.

“There was no such thing as serious gastronomic journalism,” Mr. Millau told The New York Times in 1978. “Restaurant reviews were a function of advertising.”

The approach was personal and passionate, the style “lean, mean, snappy and witty,” as the British newspaper The Independent put it in its obituary of Mr. Gault. The guide, published in book form beginning in 1972, once described “an absolutely lethal purée of peas and green beans whose strings could be woven into a bulletproof vest.”

Instead of stars, the guide awarded toques, the traditional French chef’s hats, along with a numerical rating from 1 to 20, the same system used in French schools and universities. Although a few restaurants were awarded the maximum five toques, none ever received a rating of 20, on the theory that only God achieved perfection.

In their search for new and exciting young chefs, Mr. Millau and Mr. Gault championed a new style of cooking, practiced by chefs like Michel Guérard, Frédy Girardet and Joël Robuchon, that became known as nouvelle cuisine.

In 1973 the guide issued a manifesto for the new cooking, “Vive la Nouvelle Cuisine Française,” laying down 10 commandments that began “Thou shalt not overcook,” “Thou shalt use fresh, high-quality products” and “Thou shalt lighten thy menu.”

The guide highlighted restaurants adhering to the commandments with red rather than black toques.

By beating the drum for nouvelle cuisine, the guide helped usher in the age of the celebrity chef. Its favorites emerged from the anonymity of the kitchen and, encouraged by the guide, explained their food to the public, making guest appearances on radio and television and publishing cookbooks.

“The revolutionary thing that Millau accomplished with Gault was really the style and the story,” Marc Esquerré, Gault & Millau’s editor in chief, told Le Monde this week. “They brought a human dimension to reviewing and, by acting as an intermediary between the customer and the restaurant owners, did a lot to bring these two worlds together.”

Mr. Millau was born Christian Dubois-Millot on Dec. 28, 1928, in Paris to Paul Dubois and the former Anne Masur, a Russian émigré. The birth was not registered until Jan. 1, leading to confusion in some sources. The surname Millot, the basis for his pen name, was his paternal grandmother’s maiden name.

After taking courses at Sciences Po, a leading university in Paris for political science, he set his sights on a career in journalism, although his internship at Le Monde came to grief when he misspelled François Mitterrand’s last name in an article on local elections. He landed on his feet at Opéra, a literary journal edited by Roger Nimier, a leader of the conservative literary group known as the Hussars.

Mr. Millau later described this milieu in “Galloping With the Hussars: In the Literary Whirlwind of the Fifties” (1999), which the French Academy awarded its grand prize for biography, and in the memoir “Paris Told Me: The Fifties, End of an Era” (2000).

In 1959, he married Arlette Conrad, who died last year. He is survived by two sons, Jérôme and Alexis; a daughter, Marianne Dubois-Millau; and five grandchildren.

Mr. Millau was a deputy editor of Paris-Presse, a lively afternoon newspaper, in the early 1960s when he met Mr. Gault and assigned him to write a weekly column on food and travel. The Julliard publishing house later issued a collection of the columns in book form and then asked the two men to write a Paris guidebook.

“Guide Julliard de Paris,” published in 1964, sold more than 100,000 copies. Odyssey Press brought out an American edition a year later. “Its style is breezy but authoritative — and it often bites back at the cuisine,” Life magazine wrote in 1967.

The two men produced a series of guidebooks for Julliard before starting “Le Nouveau Guide Gault-Millau.” Early on the guide dealt only with restaurants in France, but in 1981 a New York guide was published, followed by guides to Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Mr. Millau and Mr. Gault sold the guide to the magazine Le Point in 1983. It later went through many changes of ownership. In recent years Millau-Gault guides to dozens of countries around the world have been published.

With the business sold, Mr. Millau turned his attention to writing books. After learning that his maternal grandfather had been a Russian Jew, and that several of his family members had been sent to labor camps, he wrote the family history “Greetings From the Gulag: Secrets of a Family” (2004). His other books include “A Lover’s Gastronomic Dictionary” (2008) and a rollicking memoir, “Rude Journal: 2011-1928,” published in 2011.

Mr. Millau took great pleasure in stirring up trouble and laying down the law. After he feuded with Paul Bocuse, a former ally whose namesake restaurant near Lyon had always received 19 points, the guide awarded a rival 19.5 points. Later it named Mr. Bocuse one of its chefs of the century.

“What authorized us to decide and to make ratings in such a categorical fashion?” Mr. Millau said to Jean-Robert Pitte, the author of “French Gastronomy: The History and Geography of a Passion” (2002). “Let us be frank: absolutely nothing.”